Nabokov Sighting: Mary Karr's The Art of Memoir

From Mary Karr's The Art of Memoir:

"If I didn't have to pay out the wazoo to quote from better books than my own, I'd have way more Nabokov in here."

Nabokov Sighting in Knausgaard's American Travels

Karl Ove Knausgaard travels across America, retraces Norwegian and Viking trails across the country, makes this observation: "I loved it not only because I had finally seen something in the United States that Humbert and Lolita could have seen — a fabulous entry for Nabokov’s catalog of American monuments, wonders and reconstructions — but also because it struck me that the image of reality that this particular reconstruction presented was, in a curious way, absolutely true."

From My Saga, Part 2.

Part 1 is here.

Sighting: Nabokov's Flamboyant Footnotes in the New Yorker

More recently, footnotes have been employed to postmodern effect: Vladimir Nabokov and David Foster Wallace used them flamboyantly; writers such as Nicholson Baker applied them from a softer palette.

From Nathan Heller's "Save Footnotes" in the New Yorker

Sighting: Nabokov in "Finding the Words"

By that time, Gabriel had developed a series of tics. “He had a cough that was a tic,” Hirsch said. “And a way he used to run his hands over his face.” His parents took him to a psychiatrist, who sent them to a colleague, “a specialist who had the Nabokovian name Dr. Doctor,” Hirsch said.

From Finding the Words, a profile of Edward Hirsch and the book-length poem about his son Gabriel, in the 4 August 2014 New Yorker.

Sighting: Best Last Lines

Clickhole's Best Last Lines of Famous Novels, with Lolita last on the list. (Clickhole should require no explanation, but here's one just in case.)

Sighting: "Signs & Symbols" for the Internets

“You have the incorrect number,” she texted. “Delete this number please.” (Part of Ka Semenova's "Classic Russian Writers for teh Internets")

Goose Island's Lolita

According to the company, Lolita is "a pink rose colored Belgian style pale ale fermented with wild yeast and aged on raspberries in wine barrels. Aromas of fresh raspberries, bright jammy fruit flavors and crisp, refreshing body make Lolita ideal for beer drinkers fond of Belgian Framboise." It's been around for a few years, so the stock of underage-drinking jokes must already be exhausted, I'm betting.

Speak, Little Failure: Nabokov in Gary Shteyngart's Memoir

Nabokov makes a number of appearances in Gary Shteyngart's Little Failure, a funny, deft, super awesome memoir:

I twirled the pages of the monumental Architecture of the Tsars, examining all those familiar childhood landmarks, feeling the vulgar nostalgia, the poshlost' Nabokov so despised. Here was the General Staff Arch with its twisted perspectives giving out onto the creamery of Palace Square, the creamery of the Winter Palace as seen fro the glorious spike of the Admiralty as seen from the creamery of the Winter Palace, the Winter Palace and the Admiralty as seen from atop a beer truck, and so on in an endless tourist whirlwind. (7)

In 1999 I am employed as a grant writer for a Lower East Side charity, and the woman I'm sleeping with has a boyfriend who isn't sleeping with her. I've returned to St. Petersburg to be carried away by a Nabokovian torrent of memory for a country that no longer exists, desperate to find out if the metro still has the comforting smells of rubber, electricity, and unwashed humanity that I remember sop well. (15)

As I am being tossed up and down by the many weak Oberlin arms, am I thinking of the book I have just read -- Nabokov's Speak, Memory -- in which Vladimir Vladimirovich's nobleman father is being ceremonially tossed in the air by the peasants of his country estate after he has adjudicated one of their peasant disputes? (261)

The nostalgia that Nabokov thinks is vulgar poshlost', but that we as boys of nineteen and twenty are not yet ready to dismiss out of hand? (263)

And I am standing there holding my hand as a bearded, academic-looking man walks a set of Welsh corgis down State Street, a mirror of some earlier time and place -- summer break, North Carolina -- that should have pleased the early Nabokov so. (302)

I twirled the pages of the monumental Architecture of the Tsars, examining all those familiar childhood landmarks, feeling the vulgar nostalgia, the poshlost' Nabokov so despised. Here was the General Staff Arch with its twisted perspectives giving out onto the creamery of Palace Square, the creamery of the Winter Palace as seen fro the glorious spike of the Admiralty as seen from the creamery of the Winter Palace, the Winter Palace and the Admiralty as seen from atop a beer truck, and so on in an endless tourist whirlwind. (7)

In 1999 I am employed as a grant writer for a Lower East Side charity, and the woman I'm sleeping with has a boyfriend who isn't sleeping with her. I've returned to St. Petersburg to be carried away by a Nabokovian torrent of memory for a country that no longer exists, desperate to find out if the metro still has the comforting smells of rubber, electricity, and unwashed humanity that I remember sop well. (15)

As I am being tossed up and down by the many weak Oberlin arms, am I thinking of the book I have just read -- Nabokov's Speak, Memory -- in which Vladimir Vladimirovich's nobleman father is being ceremonially tossed in the air by the peasants of his country estate after he has adjudicated one of their peasant disputes? (261)

The nostalgia that Nabokov thinks is vulgar poshlost', but that we as boys of nineteen and twenty are not yet ready to dismiss out of hand? (263)

And I am standing there holding my hand as a bearded, academic-looking man walks a set of Welsh corgis down State Street, a mirror of some earlier time and place -- summer break, North Carolina -- that should have pleased the early Nabokov so. (302)

SIGHTING: Sharma on Nabokov on Chekhov

My great breakthrough came about three years ago. I was reading Chekhov to see how he controls present tense and to see if I could copy some of his solutions. Chekhov relies especially heavily on certain aspects of our senses. For example, he uses sound, smell, and feel much more than he uses visual details. Nabokov said that there is an even, gray tone to Chekhov, and this arises from his restricted reliance on the eye. Events appear to be occurring in darkness.

From Akhil Sharma's A Novel Like a Rocket in The New Yorker.

SIGHTING: Nabokov Wins One for the Islanders

Andrea Pitzer, author of The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, wrote an exceedingly funny McSweeney's bit where she replaces the eponymous hockey-player with the writer: Nabokov Wins One for the Islanders.

(This is not, incidentally, the first time Nabokov appears in McSweeney's. See also Nabokov Didn't Have to Put Up with Payroll and Less is Best, Mr. Nabokov.)

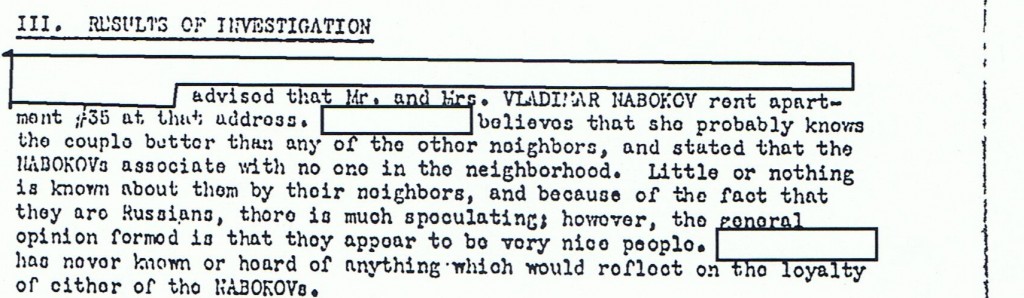

VN SIGHTING: "They appear to be very nice people."

From the blog associated with Andrea Pitzer's awesome The Secret History of Vladimir Nabokov, excerpts from an FBI report on Vera and Vladimir newly arrived in the States. The takeaway? "The NABOKOVs associate with no one in the neighborhood," but "they appear to be very nice people." Very nice people indeed! And happy belated birthday, VN!

Sightings: Nabokov at Cornell and Harvard

|

| Isaiah Berlin |

Nabokov is asked for translation help from a lovestruck Isaiah Berlin. Frances Assa summarizes what happens next:

I’ve been reading Michael Igniatieff’s biography of Isaiah Berlin. At this time (1949) Berlin was a pleasant but sexless Oxford don who suddenly, at age forty, fell violently in love. While teaching at Harvard that year, he was translating Turgenev’s First Love into English and unsure of how to translate the hero’s sudden rush of feeling when the beloved responds to his interest. Ignatieff tells us that Berlin was asking friends if it was correct to say “that your heart ‘turned over’ when your loving glance was first returned? Or should he say that the heart ‘slipped its moorings’?” and totally misses the comedy when he reports what happened when Berlin asked Nabokov for help:

"While at Harvard, Isaiah actually consulted Vladimir Nabokov—then a research fellow in Lepidoptera at the Harvard zoology department—on how to translate this particular passage. Nabokov’s suggestion—‘my heart went pit a pat’—left Isaiah unimpressed. Finally, he settled on ‘my heart leaped within me’."Nabokov quizzes a student, the student flails and provides a wildly erroneous answer, and the following ensues:

Only after the exam did I learn that many of the details I described from the movie were not in the book. Evidently, the director Julien Duvivier had had ideas of his own. Consequently, when Nabokov asked “seat 121” to report to his office after class, I fully expected to be failed, or even thrown out of Dirty Lit.

What I had not taken into account was Nabokov’s theory that great novelists create pictures in the minds of their readers that go far beyond what they describe in the words in their books. In any case, since I was presumably the only one taking the exam to confirm his theory by describing what was not in the book, and since he apparently had no idea of Duvivier’s film, he not only gave me the numerical equivalent of an A, but offered me a one-day-a-week job as an “auxiliary course assistant.” I was to be paid $10 a week.

The full story for the above quote comes from Edward Jay Epstein's An A From Nabokov in the New York Review of Books. The first quote comes from Frances Assa's post to the Nabokv-L Listserv.

Sighting: Mantel and Pnin

From Ian Crouch's Hilary Mantel and the Pitfalls of the Public Lecture:

She might have suffered the transportation indignities of Nabokov’s poor Professor Timofey Pnin, who, when we meet him, is seated comfortably in a compartment on what we learn is the wrong train, on his way to deliver a lecture—“Are the Russian People Communist?”—to the august ladies of the Cremona Women’s Club. He soon learns of the mistake, too, and a conductor sends him from the train to wait for a promised bus. What follows qualifies, as the narrator promises, as “still better sessions in the way of humor.”

She might have suffered the transportation indignities of Nabokov’s poor Professor Timofey Pnin, who, when we meet him, is seated comfortably in a compartment on what we learn is the wrong train, on his way to deliver a lecture—“Are the Russian People Communist?”—to the august ladies of the Cremona Women’s Club. He soon learns of the mistake, too, and a conductor sends him from the train to wait for a promised bus. What follows qualifies, as the narrator promises, as “still better sessions in the way of humor.”

Sighting: David Foster Wallace's Roll Call

Adam Plunkett's N+1 memoir and appreciation of David Foster Wallace as a teacher features this Nabokov-minded bit:

It took a student a few seconds to answer when called on “Joseph Reynolds, light of my life, fire of my loins” (name changed to protect privacy). My own soft underbelly was spoken (if not written) politeness, a Midwestern habit of deference and sorrys and if-you-don’t-minds my Midwestern teacher invariably mentioned or mocked or prodded in a mild recursive torment, recursive because politeness tends to be polite about itself.

It took a student a few seconds to answer when called on “Joseph Reynolds, light of my life, fire of my loins” (name changed to protect privacy). My own soft underbelly was spoken (if not written) politeness, a Midwestern habit of deference and sorrys and if-you-don’t-minds my Midwestern teacher invariably mentioned or mocked or prodded in a mild recursive torment, recursive because politeness tends to be polite about itself.

VN Sighting: Michael Chabon on Wes Anderson's Nabokovian Worlds

In this lovely essay for the New York Review of Books, Michael Chabon notes the parallel scale-world-building impulses of Vladimir Nabokov and Wes Anderson:

Vladimir Nabokov, his life cleaved by exile, created a miniature version of the homeland he would never see again and tucked it, with a jeweler’s precision, into the housing of John Shade’s miniature epic of family sorrow. Anderson—who has suggested that the breakup of his parents’ marriage was a defining experience of his life—adopts a Nabokovian procedure with the families or quasi families at the heart of all his films, from Rushmore forward, creating a series of scale-model households that, like the Zemblas and Estotilands and other lost “kingdoms by the sea” in Nabokov, intensify our experience of brokenness and loss by compressing them. That is the paradoxical power of the scale model; a child holding a globe has a more direct, more intuitive grasp of the earth’s scope and variety, of its local vastness and its cosmic tininess, than a man who spends a year in circumnavigation.Chabon himself is no stranger to world-building, or to Nabokovilia: he has made Nabokov references in Wonder Boys, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, and in The Yiddish Policemen's Union.

Sighting: Nabokov Tweets!

Nabokov! On Twitter! See what he's saying. Brilliant idea, and hats off to whoever came up with it.

VN Sighting in J. Winterson Memoir

I had two English teachers. The main one was a sexy wildman who eventually married one of our classmates when she managed to turn eighteen. He said that Nabokov was truly great and that one day I would understand that. "He hates women," I said, not realizing that this was the beginning of my feminism.

"He hates what women become," said the wildman. "That's different. He loves women until they become what they become."

And then we had an argument about Dorothea Brooke in Middlemarch, and the revolting Rosamund, whom all the men prefer, presumably because she hasn't become what women become...

The argument led nowhere and I went trampolining with a couple of girls who weren't worried about Dorothea Brooke or Lolita. They just liked trampolining. (122-3)

Kermit & Kinbote

It's always delightful to see Nabokov referenced. It is particularly delightful to see him referenced in a review of the new Muppets movie:

When Gary brings his ultra-perky girlfriend, Mary (Amy Adams), on a trip to Los Angeles, Walter tags along too, in great anticipation of visiting the Muppets' studio and meeting, in Vladimir Nabokov's phrase, "beings akin to him."

Sighting: Nicholson Baker on Steve Jobs

Nicholson Baker nods at Nabokov in his Steve Jobs eulogy for the New Yorker:

We’ve lost our techno-impresario and digital dream granter. Vladimir Nabokov once wrote, in a letter, that when he’d finished a novel he felt like a house after the movers had carried out the grand piano. That’s what it feels like to lose this world-historical personage. The grand piano is gone.Read the rest of the piece at http://www.newyorker.com/talk/2011/10/17/111017ta_talk_baker#ixzz1bF6x4se6